Two papers I found on the web on airfoil-testing tell a consistent story – Lift/drag ratio degrades as the Reynolds number decreases. Reynolds number in these tests is defined as: (air density)*(speed)*(airfoil chord)/(air viscosity).

They both describe their work as low-speed experiments, with the lowest Reynolds number of around 60 000.

The data for my simple aluminium gliders are:

- density 1.2kg/m^3

- speed 7m/s,

- chord 25mm

- air viscosity 18E-6 Ns/m^2.

This gives Re = 11 666 – much lower than the tests at the lowest Reynolds number.

With these calculations I might have expected the steep glide angles I found with my tests with my simple aluminium gliders.

But how come the paper aeroplane Suzanne flies 68m? Wouldn’t it need a reasonable glide angle to do this?

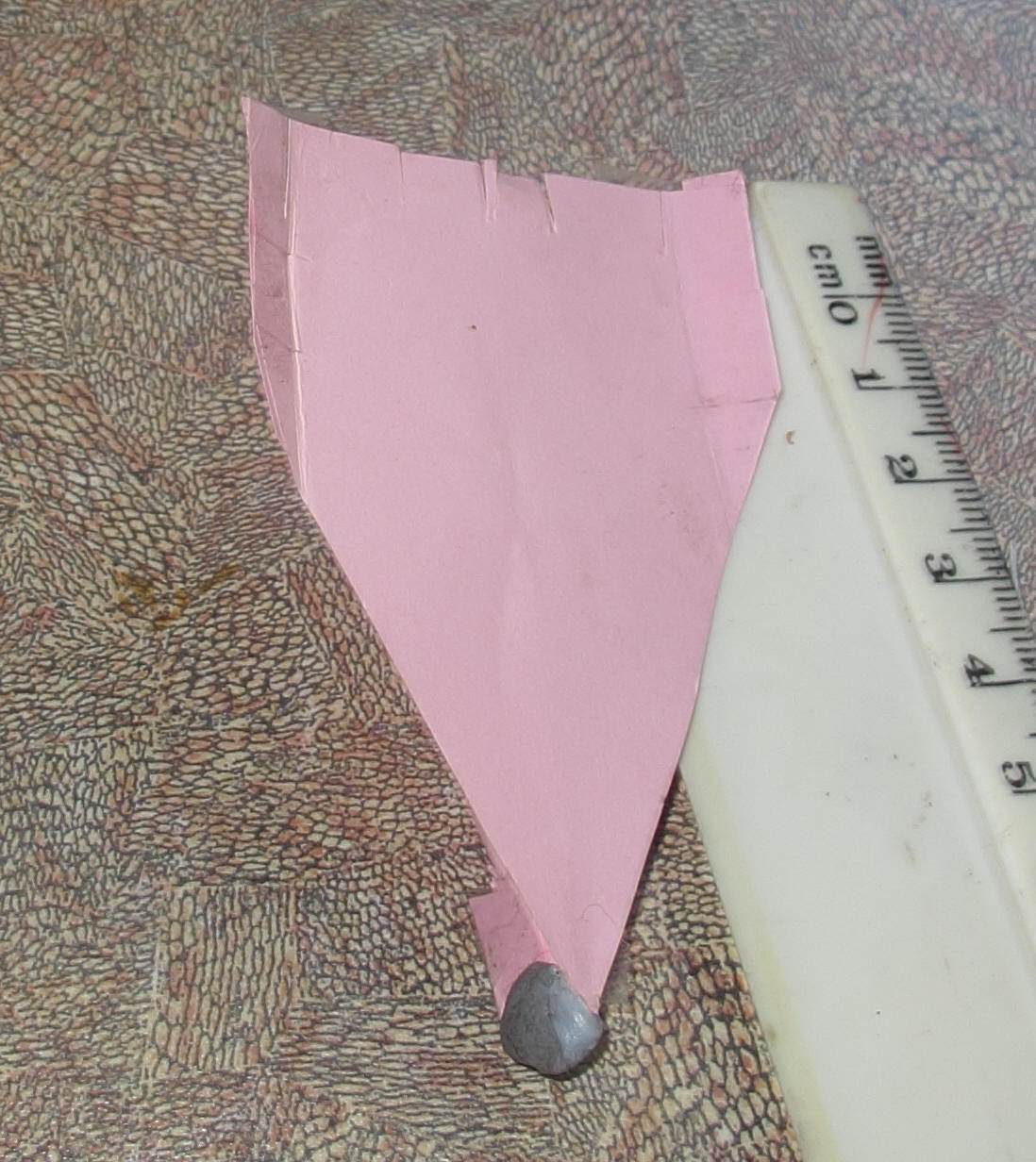

I decided to make a very small delta glider.

I made it out of copy paper and halved all the measurements from my previous delta gliders (so it worked out at roughly half the size of Suzanne in all dimensions).

I haven’t tried estimating the speed yet, but it’s probably about the same as the previous ones.

As usual with these small model gliders, setting them up is a fiddle, but when the adjustments came together it did fly surprisingly well. Its glide angle seemed about the same as the basic aluminium glider. When launched with an elastic-band launcher it easily covered 10m indoors.

I don’t quite know what to make of all this, but it has been fun.